Chrome’s “Link to Highlight”. . .wait, don’t go just yet!

Chrome’s newish (it has been in beta for a while) “link to highlight” (hereafter “L2H”) brings to the Internet a feature common to more…

Chrome’s “Link to Highlight”

. . . wait, don’t go just yet! (a tangled yarn)

Chrome’s newish (it has been in beta for a minute) “link to highlight” (hereafter “L2H”) brings to the Internet a feature common to more robust but little-used hypertext systems like Ted Nelson’s Project Xanadu, or Craig Tashman’s LiquidText. L2H allows a browser (as in the person browsing) of a text-based website to highlight a chunk of the text and link directly to it using a specialized URL. When first introduced, Google called the feature “fragments” and touted it as something new they had invented rather than a piece of hypertext history proposed in 1963. L2H should become part of the HTML standard. Actually, it should have been in HTML1.0, along with a much more robust history function, meaningful linking, incoming as well as outgoing links, and an emphasis on speed over features, but we will get to that.

Maggie Appleton has a great (yet, ironically, unfinished) overview of Nelson’s design patterns in Project Xanadu. Let’s link to it by using a pale shadow of one of his ideas, transclusion, discussed below.

L2H is one of the several features inexplicably excluded from the HTML standard, whether intentionally or by oversight. It makes the web more powerful for both authors and readers. Functionally, it is equivalent to being able to quickly make a link to a quote that is part of the page that the link refers to and then executing a search for the quote in the destination page once you get there. If you are using Chrome version 90 or above, many of the links on this page use the feature.

I think the long neglect of this feature in HTML comes from the idea that authors are somehow controlling how hypermedia gets read. They aren’t. If you write an HTML page, you can include internal hashtag anchors on the page that others can link to by adding the name of the anchor with a hashtag in front. For example, http:mypage/thispage.html#thatpart would link to the part of thispage.html at which the author considerately placed a tag named thispart for anyone who knows it is there (albeit invisibly) to link to, most often the same author. But like horses and water, the author can provide the links, but making the reader click is another thing altogether. One neglected reason for this is that links are slow. We’ll take this up below in more detail.

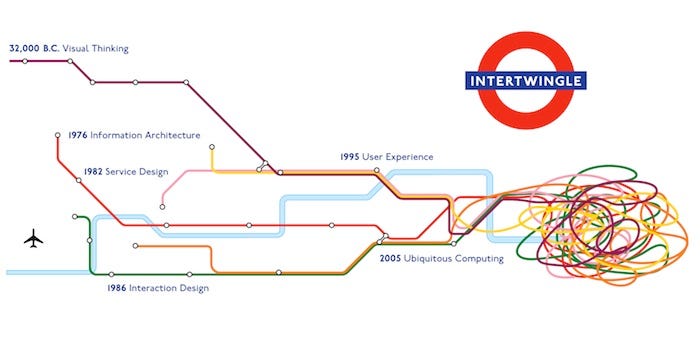

The problem with this model is that knowledge is not the taxonomy that authors create for us. Knowledge is, in Nelson’s wonderful 1974 neologism, deeply intertwingled. To demonstrate, I can report that I spent 45 minutes, which I shall never get back, finding the 1997 version of Project Xanadu in the world’s most misplaced idea for a search engine, the original Yahoo taxonomy. Of course, Project Xanadu is filed under “Top:Computers and Internet:Multimedia:Hypermedia” which seems like a good location only once you already know it is there. The reason for this difficulty is one aspect of intertwingularity: There are perhaps infinite other locations in the taxonomy that would have made just as much sense.

In practical terms, this makes things like the semantic web, the Dublin Core RDFs, and OWLs — all of which attempt to put an authored structure on knowledge — doomed to be ever incomplete and obsolete before they are constructed. All of these are created with key value pairs, like “name: Rich” which can be nested so that a value is a key and a key can contain many values (like “name:(First: Rich; Last: Rath)).”

The semantic web, if it embraced intertwingularity rather than seeking to conquer it, would have much to offer. For example, I advised on a project where the author followed various women singing blues cover versions and tracking the versions through time. The narrative was good, but she hoped to take the RDF, which was already in the content management system (Omeka in this case) and have the info for singers and covers come up every time a name of a person or a song was moused over. Unfortunately, even though that data are there, in the right format, developers already knew that we would only want the RDF output in full tables, so the task was impossible in Omeka. I went to the trouble of installing SemanticWiki, an RDF-friendly flavor of MediaWiki (the platform that Wikipedia runs on), which could — with some adjusting — output the data for one key:value pair inline rather than all of them, but it would have involved moving the project completely from Omeka, where it was finished, onto SemanticWiki. Rather than thinking about how to open up the data for people to use it, RDF almost universally creates tables because that is what the designers think it should be used for. Intertwingularity moots this conceit.

The initial HTML variant of hypertext (the semantic web was supposed to be Web 2.0) has been unable to grasp intertwingularity even as it indexes it, a sort of fundamental hubris that we can date in other sciences at least back to Linnaeus. Evolutionary biologists are on the forefront of struggling with Linnaean taxonomy — the categories for species, phylla, and — not so much any more — races — to the point that some in the field think that the ongoing questioning of it is tantamount to vandalism of the life sciences, portending imminent but avoidable deaths, and threatening the underpinnings of science itself. Hypertext can subvert these hierarchical categorizations with a single link, like from a frog (species: amphibian, name: Pepe) to people who believe whites are an actual biological race which should dominate the world (species:human, pseudo-race: white, belief:nationalism). But don't get too comfy with the idea of hypertext as emancipatory just yet.

In web developer culture, the hyperlink (a term usually traced back to Vannevar Bush’s 1945 idea of a “memex,” but first proposed as a concept by, yet again, Nelson in 1963) is the main determinant of relations between web pages. The innovation of Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin was to understand the failure of category-based strategies for finding things on the web and to replace it with an index ranking based on the missing incoming HTML links instead of the author’s outgoing ones: this insight became geek-famous as the PageRank algorithm at the heart of Google’s first decade or so.

The Google search engine made it possible, in a clunky way, to move control of hypertext browsing out of the hands of authors and into the hands of readers. Highlight a word, right click, and google away. Searching moved the locus of the link from the page to the mind of the reader. This also, perhaps without realizing it, moved browsing from the authors’ control to the readers’ (but wait, don’t go just yet).

L2H, still operating in the realm of the author, allows authors to specify parts of the link destination exactly, without needing the target author’s permission and foresight to do so. The interesting part comes when it gets combined with ubiquitous social media authorship, which can now cut right to the chase instead of providing references to a full page. This addresses intertwingularity by allowing anyone to choose freely what on a target page is linked to, whether the author considered it to be a main idea or not. LoL, and it was available in pre-WWW hypertext as a matter of course, including Xanadu and the DOS hypertext linked below.

Let me give an example of intertwingularity and the value of L2H from my dissertation research in the 1990s. I was basically working in a field that did not yet exist for all practical purposes until the early 2000s, sound studies. There were a half dozen or so of us at most at the time. When I went to new research libraries, I had to explain that there was not really a topic heading for what I was doing, so the library classification was not helpful. Perhaps second only to biological taxonomy, library classification attempts to organize all knowledge. Yet, I could not hope to find anything by either the catalog system or by subject index. I resorted to a strategy of asking for types of documents — diaries, depositions, things like that, and then just skimming through them listening for sound references.

Imagine a 1990s where my sources were in full text online and I was writing my dissertation in hypertext — the latter was true and led to some dark comedy on the job front until I pulled a traditional dissertation with a beginning, end, chapters, and all, from the hyper version. In this imaginary 1990s, it would not help for me to make a hyperlink to volume 7 of the Winthrop Papers, I wanted to drill a little deeper, with more granularity, getting to just the part about a Swiss Canton’s use of bells to scare off wolves. The finding of the material exceeded the library’s ability to pre-classify, and the target of my linking had no ability to get to what I wanted — it simply returned the whole page, which is about wolves, not sound.

L2H makes granular connection possible. When I need to cite how Massachusetts towns were contemplating using bells to organize against wolves in 1635, instead of linking to the whole volume and leaving it to the reader to dig for the details, in Chrome 96 I can link right to it. This takes another piece of hypertext linking out of the hands of the author of the linked-to piece and puts it in the hands of anyone. Hypertext ceases to be something that only authors can do — and only to their own pages ahead of time — and opens the linking doorways to everyone at a much finer calibration.

Nelson’s idea of hypertext had this system built-in, with two-way links where a reader could see what else linked to a passage as well as what the author thought to link. This was done through another of his inventions, the idea of transclusion as a way of quoting. Additionally, Nelson’s Xanadu addressed the vexed question of hypertext authorship by including a system of micropayments: When I cite your work, I do so by paying you a fraction of a penny. Why, then, are we not browsing Xanadu instead of HTML? Well, unfortunately, Ted’s release schedule was a little slower than Tim Berners-Lee’s— Nelson did not have a functioning version of Xanadu on the Internet until 2014.

The conclusion I am drawn toward is that the HTML standard with its bare unidirectional links is somewhat of an impoverished concept. Nonetheless, the reason I took half an hour to find Project Xanadu in 1997 Yahoo was that to 90s developers, hypertext meant the World Wide Web, and the World Wide Web meant html <a href=”blah.html”>blah</a> as if no other forms of hypertext existed.

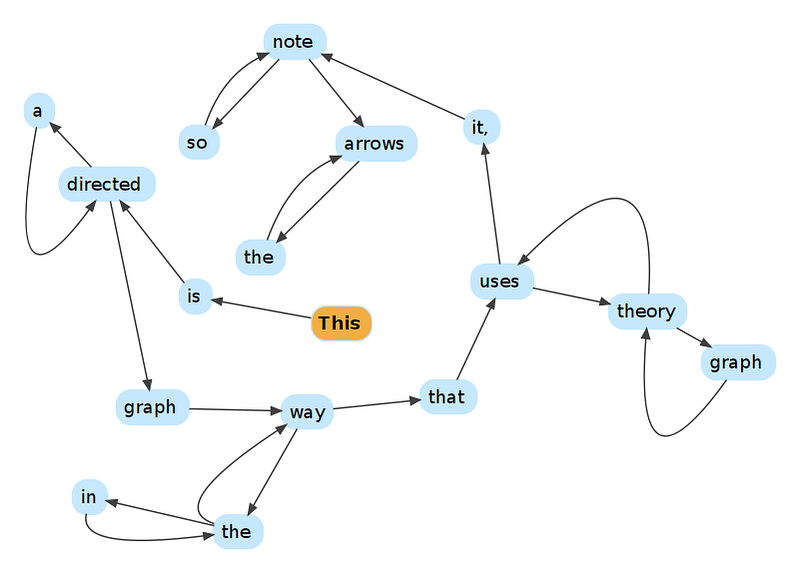

The layout of all HTML-based hypertext is what is called a directed graph. The graph in this model is not the Cartesian one we grew up with in geometry, but a network comprising nodes and links (the latter called edges in graph theory). The links point only in one direction and if you want to understand the links coming to a page rather than going out from yours, you have to graph the whole graph, in this case the Internet, which is what Google does. In the above example, consider it to be made of a set of static web pages on different sites, with all the links made by the various authors. When you are on page “way” in HTML, there is no HTML way to tell that “graph” and “the” are linking to “way.” A web page only shows the outgoing from links (“the” and “that”), even if the other page is linking back (“the”).

The nodes and links in any graph, directed or not, resonate with my humanities and social science background in interesting ways. I like to think of nodes as being “nouny” — they are things, and produce a tangible unit of information, useful or not. Butterflies pinned to a board. This is complicated in the back of the house by dynamically-created web pages that are put together on the fly from databases, like WordPress and many other content management systems, but other than being a little slower to load, they appear the same to a browser. They create nodes that are then linked together with hyperlinks.

Links, in my formulation, are a bit more “verby” — they do things, defining relations and so forth, butterflies fluttering by. But in HTML, there is little more to say than that links connect, as if for your language you have as many nouns as you can think of, but your only verb is CONNECT. The cultures of web development are mostly concerned with the “serving” of “content,” — the nouns/pages, written by an author, a construct right out of the print era — and served to a “client,” namely the browser/reader as consumer. Admittedly, this is the hypertext transfer protocol, the HTTP layer, not HTML itself. The latter sits on top of the former and tends to hide the server-client relationship.

Relationships in HTML are just connections, nonreciprocal at that, with no other meaning. The anchor text discussed above, hover previews like in Wikipedia links, or Facebook’s link previews, all try to remedy this somewhat, but the directed graph behind Facebook and all the web has little of the robustness of the nodes. In fact, the newer variations still leave the link impoverished, just giving a teaser of what the destination is rather than providing verby meaning to the link. What kind of relationship is it, then? As if Zuck’s awkward social ineptitude were captured in code: you have one type of connection, a friend (or a link in places other than FB), and that is that. The nodes/friends can be categorized into groups like family, acquaintance, and so forth, and these nodes can be wondrously filled with any linked stuff/information/content, but the link is always just “friend” whether it is mom or that kid who found you from grammar school or college who you never really knew anyway. Facebook might want you to categorize the relationship into a constricted set (good friends, family, acquaintances, or even simpler and more dysfunctional, followers and following). Beyond that, the notion of relations is impoverished. The endless meanings that are the moving parts of relations, defined by action, are missing.

Beyond FB, HTML has none of the reciprocity that can be found in even the most mundane human relationship. It is just “you talking” with no way of listening (comments, maybe, eventually, if you are popular?) when you are authoring, and vice versa when browsing. Sitting in on many web development meetings, the designer often does not care or mention who is actually reading what. The assumption is that the designers make a structure out of things they know and people will come and “navigate” it, perhaps having the troublesome ability to comment, or lacking that, a link to contact the “webmaster.” Yeesh.

The only place where this changes is when companies seek to monetize popularity, like on YouTube or TikTok for example. Then the popularity contest gets real, but none of these services are interested in creating meaning through relationships. Their concern is in monetizing the relations. But we progress as a whole through the lowest common denominator: So-called “clickbait” providing more meaning in its links, along with more surveillance and tracking (setting aside any notion of truth value). Unfortunately, this surveillance detritus is where the concern about linking in any more robust sense is taking shape, which means that whatever more robust versions of linking prevail, they will carry with them a bunch of tracking garbage serving to monetize your jumps, since that, not meaning making and relationship building, is their primary purpose.

How to boil a frog

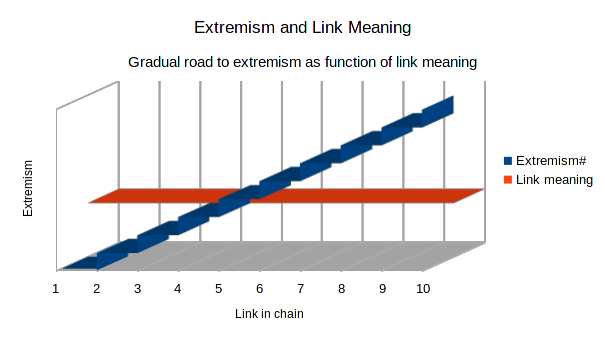

Although links approach meaninglessness — they mark connections, not relations except in the most mundane sense of the word — their lack of meaning has some unfortunate real-world effects that are used to gradually introduce people to extremism, like the apocryphal frog slowly brought to a boil. In the graph above, links remain the same as target content grows gradually more extreme. In this series of 10 links, the content starts out as not being extremist at all, but each link goes to a slightly more extreme target. Links are just links, though, not a relation but merely a connection, so the link to step ten has the same meaning as the link to step two. While the frog story is dubious, the principle holds in the world of content rather than temperature. The results of gradualism combined with the lack of meaning in links are just as deadly sometimes, though. The lack of meaning in the links serves as a cover that insulates some readers from what is going on as each step grows incrementally more extreme.

YouTube and other social media introduce algorithms compound gradualism by creating links on the fly with clickbait titles that extremists, spammers, scammers understood immediately. These are touted as Artificial Intelligence, but, as I show in another post, they just provide more and more of what you want to see on the premise that you want MOAR — that is, more of the same, but moreso.

In 2012, Tara McPherson published a wonderful article about UNIX and its offspring like Linux, BSD, and cousin macOS. Linux, not coincidentally, powers most of the web (including, no doubt, this site). All the Unices have a sort of problematic core western value built into them, according to McPherson. Let’s call it atomism, or modularity. One of the Unix operating system’s first principles is for one *nix program to do one thing only, and leave open hooks so that if other programs needed to do that thing, they could hook into the program and do that without having to load up on unneeded stuff. The principle is to “Do one thing and do that well.”

This modularity is built-in to the graph that constitutes the web, with nodes as the atoms — the “one things” — and links as the hooks. The impoverished state of links described above actually comes from the atomism undergirding Western society, perhaps as far back as Democritus and definitely into things like the Linnaeus categorization of life (think of the disgraced idea of biological races as imposing atomistic separation onto a continuum and then attaching cultural values to that). The principle of “do one thing only” comes straight from the same idea of hermetically sealing things that are actually intrinsically mixed up (intertwingled).

The Unices, coming from modular logic, McPherson argues, are basically drawn from the same epistemology as racism. The programmers' notion of relations as simply connections between “atoms” in the metaphorical sense comes from this individualist modularity rather than being an accidental or coincidental circumstance. To put it bluntly (which McPherson doesn’t — her argument is much more nuanced), and somewhat facetiously: the web is racist to its core! There is some slipperiness to this argument in its strong form (which neither McPherson nor I are making to the best of my knowledge): perhaps over-enthusiastically attributing cause to correlation. But once the pattern is seen, it cannot be unseen any more than pickles can be made into cucumbers.

The place to turn for redesigning the relationships that the web allows might be with guidance and leadership of Indigenous peoples, who in general (at least to the limited extent I know) put more weight and meaning into “relationshipping” than is common in programming. They treat connections or links in the world as tying us all together in meaningful ways: all our relations, to borrow the phrase that Ojibwe scholar/activist Winona LaDuke brought to the fore. Relations and links hold societies and cultures together rather than the “nodes.”

The Indigenous commonplace to mind all one’s relations out of the past and into the future could go a long way toward addressing the atomism not just of programming, but of whole societies and social systems, particularly, to give one example, the climate crisis induced by capitalism’s need for continuous expansion. That makes for some interesting code with Indigenous scholars leading the way, such as the people at the Mukurtu platform and community.

L2H took an incredibly long time to arrive, and it remains to be seen whether it will catch hold as a browser-specific feature that eventually gets incorporated into the HTML standard. But besides the problem of one-way outgoing links and their intrinsic lack of meaning, browsers (the software) could do a few other things better. One would be to make browser history into a graph, which would help make it more meaningful than a giant unstructured list of outgoing links. I cover this from the reader’s perspective in the chunking section of my essay “How to Read Hypertext.” The tree should be editable as far as where things get placed in what order. Then it would be a useful way of comprehending the vasts swathes of information.

Sharp readers might note a contradiction between this structured learning and intertwingularity. The latter is what we browse, the terrain. The branching tree model of bookmarks would be akin to a map, and the path one takes through that map would be a route or itinerary. Looking to the image at the top of this essay, it is easy to picture intertwingularity, but if I am an ant and need to get from the tree on the left to the one on the right, I don’t walk across the whole tangle. I pick one branch or vine at a time, and if a path does not work, I retrace my steps, learning from the diversion, and choose another route, one branch at a time, on a different path. The Web Historian Chrome extension has some great ideas in this regard, but while I admire it, it has not proven to be something I use to order my thoughts about where my browsing has been. Intertwingularity means that it is impossible for an author, librarian, or archivist to predict how a reader will choose to construct knowledge from web pages, particularly since the right-click search removes the hyper-reader’s reliance on authors’ creation of links to show them where to go, as if the ant could just create a new branch to traverse at will. Yet, each of us does construct ordered knowledge, with various strategies for doing so. It is just that my structure will be idiosyncratic — as will yours — and neither will reliably be what an author puts there.

Here are some quick strategies for ordering web knowledge: You could be a “vertical” reader who reads the whole page before clicking anything. Multiple links mean going and coming back to go again, a more horizontal shuttling process. Then there is the archetypal surfing, just basically clicking through and never looking back, which is how the first generation of hypermedia consumers confused the hell out of themselves by trying to read hypertext like a book, that is, linearly. Myself, I split the difference by opening links I am interested in new background tabs as I read through the page. This has an important advantage I will discuss next, in that the pages load in the background and are ready to read when you get to them. The downside is massive arrays of opened web pages that I sometimes never get around to looking at all.

The HTTP(S) and the URLs in a link are deadly slow; too slow to keep up with human cognition. If you need to wait for a clicked-on page to appear in your browser for more than about a twentieth of a second, it interrupts your flow. I for one, take waiting into consideration before I click…do I have time to stop reading and let this new thing load? Or should I continue along without breaking stride? There have been various caching and prefetch schemes in place since the web was begun, but they never caught on with developers except in the narrow domain of scripts and CSS, which are not user-facing content. One of the chief objections comes from advertisers, who argue that prefetching pages dilutes the effectiveness of their ads and costs more by fetching pages that are not actually read. Again, advertisers come before readers. Reader eyeballs are what the ad companies sell, so they discourage prefetching.

What if you did not have to make that choice, and links were instant or nearly so? In the early nineties, before HTML had really caught on and when the “WWW” was still an exotic new thing, there were many small hypertext outfits with their own ideas. I used an obscure one called MaxThink for creating my notes, and I put together some heavily linked hypertexts this way. If you would like to try it, and see for yourself how fast links make a difference in overcoming the hesitancy to click on the World Wide Wait, here is a dated, unfinished, somewhat disorganized hypertext I wrote on the state of pidgin and creole linguistics and history in 1992 for you to try. Here is the GitHub page if you want to preview what is in the zip file before downloading. It should take about a minute or five to set up, no installation, and it should “just work” to transport you back to a little DOS time machine right in your modern one. The point of using it is to see what effect speed has on your willingness to use the arrow keys to go from one page to another when the pages load instantly rather than in seconds.

The program runs in a DOS emulator and has no graphics and does not connect to anything online. Executing a link arrives at the link target instantly. Weaving back and forth this way through a hypertext is no longer like reading separate pages at all. It becomes a seamless flow and fun to read, I hope anyway.

The twentieth of a second rule is not arbitrary; perhaps it is a hard limit for the speed of human cognition. If an audio beat plays faster and faster, it begins to lose its rhythmic quality, we instead begin to perceive it as pitch right at about a twentieth of a second. Same for vision. Once video frames occur less than a twentieth of a second apart, the magical perception of continuous motion occurs. I thought Armin Van Buuren’s song Ping-Pong did it with the ping pong balls, but a closer listen shows that it isn’t so. Instead, I provided a video of an electronic drum beat turning into a synthy sound and then slowing back down to a beat again.

Developers are for the most part more interested in laying on new features, writing dynamic web pages, calling out to a database to return and then format stuff like in reading this blog; graphics and gewgaws running in the background slow down loading, and in general, the tricks that make the text of a page appear first are generally neglected in favor of making sure the gewgaws all load successfully first — things like scripts, beacons, offsite cookies set like the Google Analytics one that cause extra loading time for every page that uses them: The page won’t load until the Google has its stuff:

Just a second…let me collect your personal info first…

… And you have broken the flow and become merely linked pages, one thing then another when it comes. A slide show instead of the movies.

Quaint, impractical suggestion based on these principles:

Load structure and text first because it is small and direct and thus fast. Reader-facing content first, local first, aim for time < 1/20 sec.

Frills, imported scripts, imported fonts, tracking and advertisements last, a half second later so, after all the local stuff has loaded. Load local before loading non-local because internet connections are a bottleneck.

“Impractical” because A) devs want to show off their code skills. Content is boring. B) advertisers and trackers know that the reason for web pages is to track, surveil, collect, and link to the rest of that data: To the people paying for the web pages (advertisers and trackers), the content that the reader comes for is secondary and cannot be made available until after the paying customers is loaded and the beacons are turned on so the data collectors don’t miss a saccade. The readers’ eyeballs and ears are the product; We are not the customers.

While I welcome H2L and hope it catches on, there are so many other things that could move web browsing up a cognitive notch from where it is today. The emphasis here has been on providing tools to let hypertext readers continue to take the craft of narrative from the often inept hands of hypertext authors and place it more firmly in the camp of the readers: speed, bidirectional linking, a user-structured history function. As it stands, HTML and its WWW kin are a monument to developer hubris at the same time as being one of the most useful things ever developed.